Some knitting projects volunteer themselves and prove as delightful as flowers you didn’t plant.

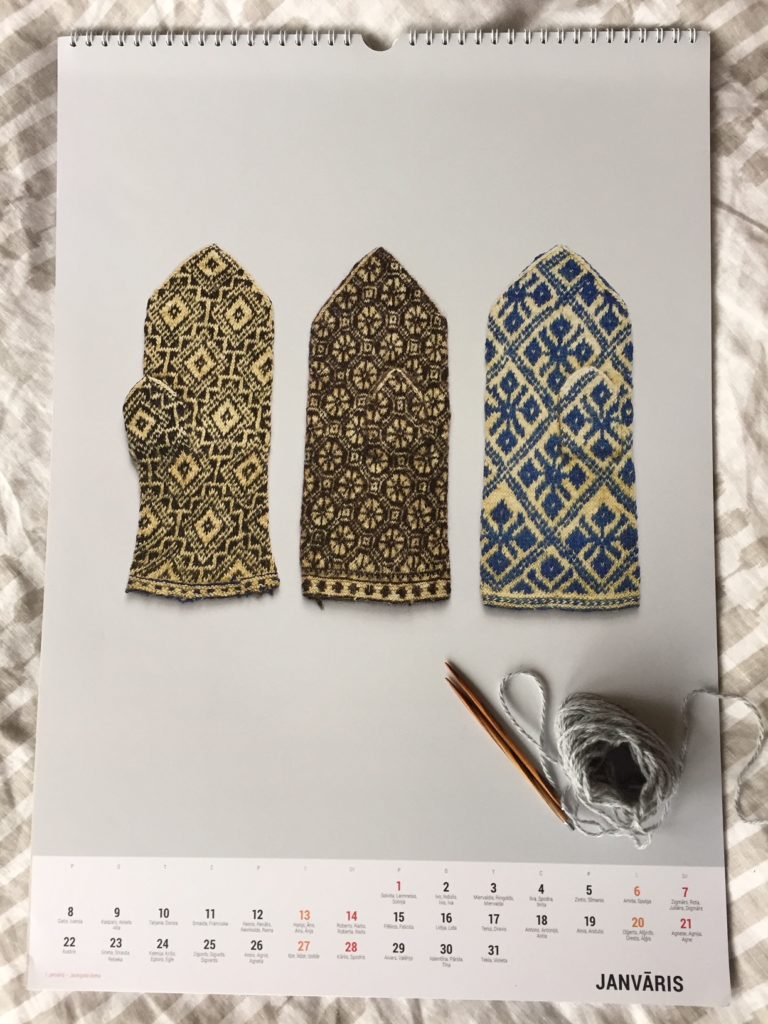

The vision of a new design can grow from almost any seed—from the yarn itself, from nature, from history, and sometimes from all of these braided together. In April I found I couldn’t set aside the remnants of a skein of Spincycle Yarn I’d used for a hat for my father; the earthy tones still wanted my attention, and they wanted prominent display on the yoke of a sweater. As it was spring, I had flowers dancing before my eyes, and as I was leafing through a book of Scandinavian mitten designs, I chanced across a thumb motif I thought might be the right scale for a child’s sweater if worked at the larger gauge I was imagining. I fossicked in my stash for likely partners for the Spincycle—namely a main color—and found three plump fingering-weight skeins of Catskill Merino in the springiest watercress green. Another remnant skein of heathered brown Raumagarn was just right for the flowers’ roots (and I loved that the flowers had big strong roots in the original mitten). I knew I hadn’t enough of the Spincycle to carry me through the foliage in the motif, but lo, there was the skein of BFL/silk I’d made in my first year of spinning practice, featuring the same olive and golden greens with burgundy. It could easily pick up where the Spincycle would leave off. I auditioned a whole raft of neutrals for the yoke background and wasn’t satisfied. Everything was the wrong weight or looked too flat or too stark against the lively color play of the handspun contrast colors. But when I popped into Wild Fibers in Mt. Vernon for some buttons, there was an intriguingly flecked pale golden skein of Noro Kumo that leapt out at me. Everything was coming together.

I’ll have to steal it back to block the button band!

In the middle of my merry progress, I learned that Catskill Merino had lost Eugene Wyatt, its founding shepherd. I wrote on Instagram, “Once in awhile in life you brush against someone with a truly original spark and it kindles something in you that burns for a long time, perhaps unnoticed. Eugene was one of those—and a good writer to boot. That I’m a shepherd now is, perhaps, a little bit due to him.” Eugene certainly expanded my sense of what kind of person might choose to devote himself to sheepkeeping. He kept one of the best blogs on shepherding, equal parts poetic and practical. He punctuated his market days selling wool and lamb at Union Square with jaunts to the cinema; he read a lot of Proust. Even in a brief conversation you could sense the depth of the living and thinking he’d done.

I think about Eugene Wyatt whenever people are surprised that we’ve shelved our city life in favor of a sheep farm on a tiny island. I think about the assumptions I once made that farmers were mostly folks who’d inherited a way of life and hadn’t escaped to anything more intellectual. Eugene made me consider that you could be a passionate intellectual and a farmer all in one. And now I know from experience that learning how to farm uses every intellectual skill you’ve got—and then some. Writing about it as well as Eugene did clarifies your purposes and precipitates beauty out of the daily soup of humble chores like mowing, moving fences, scrubbing water troughs, trimming hooves, mucking sheep sheds, battling weeds, and making up fecal slurries to count worm eggs.

Eugene and Dominique, who dyes the yarn and helps with the flock and now carries the work forward alone, were also at the beginning of my awakening to the farm-to-skein story of the wool I choose to work with. Most knitting shops weren’t carrying yarns like theirs when I took up the craft, and it was fresh and marvelous to sink my fingers into wool raised just a few hours away and dyed with botanical extracts. Since I first discovered Catskill Merino, the market for locally grown wool has really begun to flower, and that’s wonderful to see. I’ve had the chance to knit with many more single-flock yarns over the years, and I’ve loved most of them. The beautiful green skeins in Ada’s new sweater only rekindled my appreciation for the quality of breeding and craft at Catskill Merino: this is really excellent wool, terrifically soft without sacrificing character. It’s still head of the class even now that the class is larger.

The true testament? My kid didn’t take this sweater off all day when I gave it to her, even as the mercury climbed to eighty.

Someone’s going to ask when the pattern will be available. I’m going to revise the motif a little bit—maybe take out some of those three-color rows with long floats—and grade it up to adult sizes. I might make a pullover for myself. I may chart a shorter version of the flower so the yoke depth can be shallower, allowing for smaller kid sizes. I’ve got another design project on my needles right now, but I’m looking forward to picking this up in September.